The United Arab Emirates’ rulers will soon achieve a distinction they’ve long coveted. Their once sleepy stock exchanges will be home to companies valued at $1 trillion. This outsize success- the markets already ranked number 17 in the world at the end of March, ahead of Brazil and Spain-relies on the recent chart-topping performance of the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange, run by the UAE’s biggest and wealthiest city-state.

But global investors tempted to pile in face the Abu Dhabi market’s defining feature. Royal family member Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan – one of Abu Dhabi’s two deputy rulers, national security adviser of the UAE and brother to its president – dominates just about every part of its business. As of March 31, the sheikh’s companies or those he oversees had a weighting of at least 65% of the benchmark FTSE ADX General Index.

The biggest: his conglomerate International Holding Co., or IHC, which has investments in everything from Rihanna’s lingerie line to Elon Musk’s SpaceX. IHC is up more than 400-fold since 2019. The sprawling conglomerate, which traces its roots back to a fish farming firm, is now valued at almost $240 billion, more than Walt Disney Co. or McDonald’s Corp.

IHC also makes money from trading on the very exchange where it’s listed. It owns the Abu Dhabi stock exchange’s most active broker. Meanwhile, the emirate’s ADQ fund, which Sheikh Tahnoon chairs, oversees the exchange itself.

The sheikh’s influence runs even deeper. He’s the de facto business chief of Abu Dhabi’s ruling Al Nahyan family, the world’s wealthiest. And he steers about $1.5 trillion, mostly through the sovereign funds he heads. It’s as if one man directed the New York Stock Exchange as well as two-thirds of the companies in the S&P 500 stock index.

Many bankers, investors and economists say the Abu Dhabi market’s unusual structure poses challenges for global investment managers who want to profit as its main index has almost tripled since April 2020, making it the world’s best-performing major market over that period. Outsiders can struggle to get a piece of the action, because UAE nationals and companies own large stakes and hold on to them; those who manage to do so wonder if they’ll be treated as favorably as insiders.

“The interlinkages of assets and the concentration of control in Sheikh Tahnoon’s hands, despite being neither ruler nor crown prince, are unusual even by Gulf standards,” says Steffen Hertog, an associate professor at the London School of Economics, who studies the region. These ties can create economic advantages by coordinating state investors and government departments, he says. “They also raise questions about whether there’s an equal playing field with private competitors and how well minority shareholders’ interests are protected.”

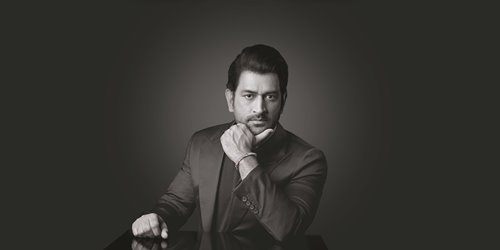

In a rare interview, IHC’s Chief Executive Officer Syed Basar Shueb says all comers have access to the company, which has directed its brokerage to work with global investors. “I don’t see why people complain that it is not open for the foreigners,” he says. “Foreign investors always go to those traditional brokers, those who cannot provide that service. I have to make sure that I feed business to my own company.” Representatives for the government and spokespeople for Sheikh Tahnoon’s other businesses either declined to comment or didn’t respond to questions.

The sheikh has increasingly come to embody the UAE’s global economic aspirations. He’s used his holdings and position to pursue acquisitions, such as a stake in Zambia’s Mopani copper mine, while pushing efforts to boost the domestic economy. The UAE’s sovereign wealth funds and business hubs reflect the ruling Al Nahyan family’s push to diversify away from oil, which was discovered in Abu Dhabi in the 1950s and represents the foundation of its wealth. The family is seeking to turn the emirate into a financial center, where titans of finance such as Ray Dalio have bought beach-side penthouses.

The UAE has long used flashy records to highlight its international importance. It boasts of the world’s tallest building (Dubai’s glittering Burj Khalifa) and the world’s fastest roller coaster (Abu Dhabi’s Formula Rossa, which gets up to 240 kilometers per hour in 4.9 seconds). The stock market reflects the Al Nahyan family’s ambitions. Members expect its rising value to attract international capital and encourage local investors to keep their money in the country, according to people familiar with their thinking who requested anonymity to discuss the rulers’ strategy.

Since 2020, through the end of March, the total value of companies listed on UAE exchanges has nearly quadrupled, to $950 billion. (Saudi Arabia’s market, at $3 trillion, remains the region’s largest.) Abu Dhabi’s benchmark index accounts for $711 billion. The rest mostly comes from Dubai, its smaller neighbor.

The UAE said in 2019 it will allow foreigners to own 100% of businesses across industries. Since late 2021, governments have sold stakes in state-owned companies to boost the exchanges and bring in investors. Dubai Electricity & Water Authority PJSC ‘s initial public offering raised $6.1 billion, attracting buyers such as BlackRock, Vanguard Group and Fidelity Investments. “Capital markets have been playing the role of the conduit, channeling investments from international markets into the local economy supported by an ambitious privatization program,” says Rami Sidani, head of Middle East and North Africa portfolio management and frontier investment at Schroders Investment Management.

Initial public offerings tied to Sheikh Tahnoon seem a surefire way to make money. Five of the 10 best-performing IPOs in the UAE since the start of 2021 have come from companies in his empire or controlled by the sovereign wealth funds he oversees. Bayanat AI Plc, his geospatial and data analytics outfit, more than tripled on its first day of trading in 2022, though it’s since given up some of those gains.

Wall Street banks organize trips to the region for fund managers to meet would-be IPO candidates, a stark change from when regional companies would seek to list in London or New York. But the difficulty of getting a decent allocation in the oversubscribed IPOs has been a source of frustration for international investors, and they often aren’t even offered many of Sheikh Tahnoon’s, people familiar with their thinking say.

“In certain instances, we feel that the intention is to attract foreign investors and promote higher international participation,” says Salah Shamma, Franklin Templeton’s Dubai-based head of equity investment for the Middle East and North Africa. “In other instances, it appears more like a redistribution of wealth within the local investor community.” Shueb, IHC’s CEO, says top priority should be given to UAE-based investors: “The local demand and local institutional demand is so high. We cannot give more than what we have.”

Global emerging-markets funds that actively select stocks have increased their exposure to the UAE in recent years, according to Copley Fund Research, but the emirates’ stocks are still slightly underweighted. Nationals hold about 90% of IHC shares, and no stock analysts tracked by Bloomberg follow the company. Shueb says he won’t pay analysts to cover IHC but that they’ll start once they fully appreciate it.

Locals also hold most of the Dubai Electricity & Water Authority and oil servicer Adnoc Drilling Co PJSC, making it more difficult for foreign institutions to execute large trades.

“Liquidity is very, very important,” and it still has a long way to go in the UAE, says James Donald, head of emerging markets at Lazard Asset Management LLC. In Donald’s view, the Middle East also ranks among the hardest for investors to get information about companies they’d like to trade.

For example, the section on financial disclosures in the IPO prospectus last year of Sheikh Tahnoon-linked PureHealth Holding PJSC, which owns health-care centers, was only five pages long and contained no management discussion of the results.

“The international standard IPO process allows for a much more thorough investor education,” says Andree Chakhtoura, head of investment banking for Middle East and North Africa at Bank of America Corp., speaking generally and not about PureHealth.

Shueb says IHC meets with many investors and this year is adding “a very active investor relations” department. PureHealth’s annual financials were due 45 days after the IPO, so the prospectus included “the bare minimum” information about the results, he says.

IHC’s complex valuations cause head-scratching among analysts and investors. Abu Dhabi has transferred the ownership of dozens of private companies to IHC, sometimes through reverse mergers. The conglomerate’s cash and cash equivalents reached $20 billion last year from $80 million in 2018, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. (Shueb says financial experts and consultants audited third-party deals.)

Investors in the UAE must be prepared for the market’s quirks. In February, IHC made a governance move that’s not likely at a NYSE-listed company. It said that a virtual entity endowed with AI capabilities would act as an “AI Observer” on its board. Called Aiden Insight, it will continuously process decades of business data and financial information, according to the company.

Ryan Bohl, senior Middle East and North Africa analyst at risk intelligence consulting firm Rane Network, says investors in the UAE may contend with less than clearly articulated policies. But the fact that so much relies on one royal provides one kind of clarity, he says: “The dirham, so to speak, stops with [Sheikh] Tahnoon.”